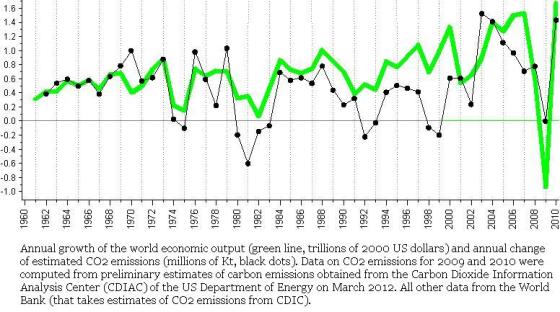

Since I started this blog ten days ago, I’ve been harping on the idea that economic growth is directly linked to carbon emissions. Research shows that recessions cause significant drops in carbon emissions, while recoveries cause significant emission spikes.

Everybody likes growth. If you are a progressive Democrat, you favor economic stimulus to bolster economic growth and the middle class. If you are a Republican, you would like to cut taxes, “reform entitlements,” and peel back government regulations to unleash the “confidence” of our job creators and stimulate economic growth. Budget reporters unfailingly cast economic growth as “healthy,” and necessary—something that everyone obviously desires. The expert economists that are featured in the press say the same thing. Read any of the coverage of the ongoing “fiscal cliff” negotiations and this will become quickly evident. It’s called the “cliff” for a reason.

I want to draw your attention to a report on “Inclusive Green Growth,” by World Bank Sustainable Development Vice President Rachel Kyte. Here is the opening salvo:

“Inclusive green growth is the pathway to sustainable development. Over the past 20 years economic growth has lifted more than 660 million people out of poverty and has raised the income levels of millions more, but growth has too often come at the expense of the environment. A variety of market, policy, and institutional failures mean that the earth’s natural capital tends to be used in ways that are economically inefficient and wasteful, without sufficient reckoning of the true social costs of resource depletion and without adequate reinvestment in other forms of wealth. These failures threaten the long-term sustainability of growth and progress made on social welfare. Moreover, despite the gains from growth, 1.3 billion people still do not have access to electricity, 2.6 billion still have no access to sanitation, and 900 million lack safe, clean drinking water. Growth has not been inclusive enough.”

Inclusive green growth is the way to save the environment and lift the world’s poorest out of poverty, says Kyte. This is the main thrust of the report. Of interest to us is a short section on growth and the developed economies.

Kyte discusses the Kuznets Curve, an economic theory that I touched on last week. The Kuznets Curve holds that income inequality will rise in developing economies (China, Brazil, India), and fall as those developing economies become fully developed (Western Europe, the United States). The Environmental Kuznets Curve holds that economic growth will become more polluting in developing economies, and less polluting as these developing economies become developed. In other words, developed economies are, like, totally awesome.

The Kuznets Curve is completely wrong, says Kyte:

“The famous Kuznets curve argument, which posits that inequality first increases and then decreases with income, is not supported by the evidence. Inequality has increased substantially in recent decades in China, but also in the United States and most of Europe. And it has declined in much of Latin America (Milanovic 2010). Some countries reduce inequality as they grow; others let it increase. Policies matter. Thus, the links between the economic and social pillars of sustainable development are generally self-reinforcing. But the story is not so simple when it comes to the economic and environmental pillars. Economic growth causes environmental degradation—or has for much of the past 250 years—driven by market failures and inefficient policies. As with inequality, overall environmental performance does not first get worse and then improve with income—no Kuznets curve here either.”

Got that? Since the beginning of the industrial revolution, economic growth has caused environmental degradation. Developed countries don’t necessarily become more environmentally-friendly or economically equal just because they are post-industrial. They have to enforce policies that accomplish those lofty goals of economic equality and environmental protection.

Why should we continue to grow wealthy, developed economies, then? Some critics have asked this very question, Kyte tells us:

“Against this backdrop, some observers, mostly in high-income countries, have argued against the need for more growth, suggesting that what is needed instead is a redistribution of wealth (Marglin 2010; Victor 2008). They point to the happiness literature, which suggests that above a country average of $10,000 to $15,000 per capita, further growth does not translate into greater well-being (Easterlin 1995; Layard 2005). While this argument has value, it remains more relevant for high-income countries, where average annual incomes hover around $36,000. Developing countries—with average income of around $3,500 per capita—are still far from the point at which more wealth will bring decreasing returns to well-being.”

The World Bank Vice President for Sustainable Development is open to the idea of halting growth in high-income countries, and then redistributing their wealth. I’m not sure whether she is talking about redistributing the wealth to poor countries, or to the poor within the high-income countries, or both. Either way, this is far more radical than anything anyone is talking about in the American media. It’s also far more rational, given the climate and resource crisis knocking on our door.

“Thus, growth is a necessary, legitimate, and appropriate pursuit for the developing world, but so is a clean and safe environment. Without ambitious policies, growth will continue to degrade the environment and deplete resources critical to the welfare of current and future generations.”

The developing countries need to grow in order to alleviate poverty and social chaos. We do not need to grow. We have lots of money, although it is distributed in a highly unequal way. Our historical record of economic growth is a major cause of the climate change fiasco. We should stop growing, and redistribute our wealth, in order to mitigate climate change and social chaos. Or so suggests wild-eyed radical, Rachel Kyte, the World Bank Vice President for Sustainable Development.

Why doesn’t anyone talk about this?